MISCELLANEOUS

This blog post was sparked off by an interesting and humorous video from the World Bank that I saw this morning (the picture above is also from the same video) which highlights a familiar problem that we face as we think about government services, particularly in two of the areas in which we work, health and education. The video is associated with a detailed report that has recently been released by the World Bank (available for free download for all those that want to read it in detail).

From what I could understand the key insight from this report is one that we act on every day in our work – empowered communities holding service providers directly accountable is an important, if not the only, tool for improving service delivery at the front line. They give some wonderful examples of schools in Jordan and Palestine, and health services in Jordan, where providers and the community working together (with the help of a local NGO like us, presumably) were able to effect a dramatic transformation in the quality of services that were provided.

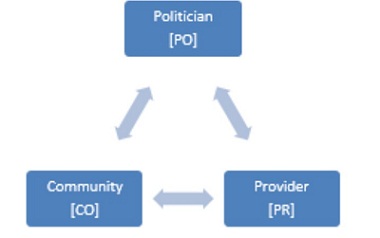

A few months ago a workshop was organised at our Delhi office on this exact issue and Dr. Stuti Khemani drew this (above) very elegant diagram for us which has three levers:

A. CO to PR (Community directly and locally engaging with front-line members of the government providers and holding them accountable)

B. CO to PO (Community through its citizens participating in the democratic electoral process to express their preferences and concerns).

C. PO to PR (Locally elected political representatives at the Village, State, and National governments engaging with the senior hierarchy of the government provider, who in turn engage with their own front-line members).

The World Bank report mentioned earlier, a lot of our work on the ground, a number of activist organisations, all express a strong preference for the first “CO to PR” lever and strongly feel that this is indeed the way forward to building high quality service provision. However, I worry about the reliance on this lever from a number of perspectives:

1. How will this scale? This presumes the continued existence of an external NGO that makes this change happen. Are there a sufficient number of such NGOs? Who will fund them? What will happen after the funding to the NGO dries up and it leaves? Who is the NGO accountable to?

2. Does the community have the knowledge to truly supervise, direct, and hold providers accountable? Do they have the power to do so in an environment where the teacher and the doctor are far more educated than they are and far better connected politically? This kind of accountability sounds very much like a market based solution – why not simply give people the vouchers and let them decide – this will give them both the power and the choice needed – what is so special about having them struggle to engage with a government provider to improve its performance? Will we not end up with all of the problems of the market (with few of the benefits) if we follow this lever to its logical conclusion (more “English Medium” schools and more “saline bottles”!)?

3. Is it really fair to ask them to do this on top of everything else that they have to contend with in their daily lives?

4. If the third lever (PO to PR) acts in the opposite direction and shields providers, will the CO to PR lever be effective? Isn’t the true problem the PO to PR lever?

In the workshop there were two alternative levers that were discussed:

1. CO to PO using regular electoral processes, which in turn activates the PO to PR lever and most importantly neutralises the reverse PR to PO lever through which politicians intervene to shield the politically important front-line providers. The key question here was that, while this is clearly a superior lever, how does one activate it? Dr. Khemani presented a great deal of her own and other research in this area.

2. A within-PR lever which seeks to introduce non-controversial (i.e., which will not trigger the PR to PO lever, the one where providers are being shielded by politicians), non-accountability-linked levers, such as daily rituals which, over time, have the effect of changing the internal norm of provider behaviour which is entirely unlinked to either the CO to PR lever or the PO to PR lever. Not much work appears to have been done with this lever and it does look promising, but it was pointed out that this work would become easier if the PO to PR lever was supportive because otherwise it would become impossible to even introduce these rituals into the system (“By all means work on improving their performance as long as there is no political backlash on me”).