LIVELIHOOD

´╗┐I am always amazed by the tribal world, which is altogether a different world resplendent with traditional wisdom and indigenous practices. Recently, many of us happen to witness how tribal women across the country voiced their concern regarding mining in certain parts of Odisha, and the solidarity they expressed in order to preserve the natural eco system and protect their rights.

It is common knowledge now that tribals yearn for identity rather than being christened as poor and needing handouts. They would appreciate minimum disturbance from non-tribals, the actions of whom are considered to be usurping their basic rights of living with nature, which is endowed with gifted resources, and which they are keen to preserve for their future. Tribals are historically known as gatherers of forest based produce, and to wean them away from primitive living habits into cultivating farm based crops is a huge challenge.

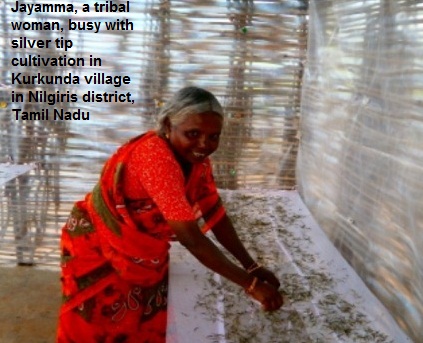

Tea came in handy in the higher elevations of Nilgiris; but the quality of cultivation practices is far from desired, mainly due to their poor exposure to modern practices and lack of awareness on innovative cultural and agronomic practices. Tea is generally considered to be a domain of big planters, belonging to large farm households, with a character of estates unlike tribal cultivating, which is in small patches of fragmented holdings for sustenance, keeping food security in mind. It is difficult to inculcate a market led approach among the Tribals as it is a completely alien concept to them.

CARE India initially organized small tribal farmers for productivity enhancement and income diversification opportunities through improved cultivation practices, and enabled tribals to grow cattle for milk and raise vegetables in their backyard, primarily to supplement their nutrition needs.

In the process, it was discovered that small tribal farms are receptive to new ideas and adaptive to improved cultural practices. CARE India partnered with Tea Board, Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) and Horticultural department to implement improved farming practices which will conserve soil, moisture and water.

Newer ways of plucking tea leaves demonstrated improved quality and standards in tea leaves production, which fetch good returns- sometimes as high as 10 times in the market- vis-à-vis conventional leaf plucking. Women also emerged as guardians of food security with the incremental income, and they safeguarded their households from vulnerabilities of the market and governance failures.

After three years of engagement, we are pleased to see small tribal farms with a high rate of adoption of cultural and plucking practices, along with diversified enterprises like dairy and maintaining a kitchen garden. These efforts supplemented tea cultivation, and addressed their food security requirements, while conserving soil and water through agronomic practices to insulate them against shocks arising out of climate change.

I could see how resilient they stand confident against climate change, as well as how they became immune to social vulnerabilities, standing tall with social prestige, and staking their claim as ‘tribal’ in the comity of a non-tribal world.

In the back drop of depletion of natural resources, the tribal farms stand tall as knowledge banks with potential to influence best practices in hill based agrarian eco system. For CARE India to have chosen tribes as its impact population to bring about social change, to give them the much required recognition and identity by addressing the underlying causes of poverty and social exclusion, has made the tribal households more resilient to social and economic vulnerabilities.

The climate change adaptation initiative for small tribal households is implemented by CARE India with the supported of Teavana in the hinter lands of Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India.